Features

Breeding

Profiles

R&D brings burbot back to Belgium

Belgian entrepreneur plans hatchery expansion after early rearing success

September 8, 2020 By Lynn Fantom

Joachim Claeyé, founder of Hatchery Aqualota in Belgium, holding a burbot. Photo: Guido Claeyé

Joachim Claeyé, founder of Hatchery Aqualota in Belgium, holding a burbot. Photo: Guido Claeyé

Joachim Claeyé started his business in a garage. Like many entrepreneurs, he shares his story with a special group of collaborators and mentors.

But Claeyé’s tech skills are in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). And his innovation is to pioneer next-generation menus with a species that was virtually extinct in Europe: the burbot (Lota lota).

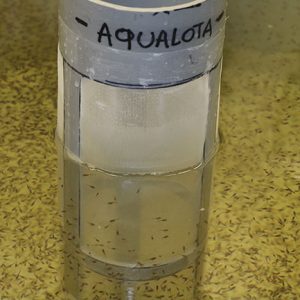

At age 20, Claeyé founded Hatchery Aqualota in Zele, East Flanders, Belgium. Now, three years later, he is expanding commercial operations in space leased from University College Odisee, where, as a student, he had participated in industry-leading research at the Aquaculture Education and Research Facility (Aqua-ERF).

This growth of Aqualota is coming at a time of increased global interest in cultivating burbot. On the other side of the Atlantic, the lab of Dr. Kenneth Cain, associate director of the Aquaculture Research Institute at the University of Idaho, has been testing how different commercial feeds affect the growth and health of burbot. “It is a really promising candidate for aquaculture,” Cain says.

Aquaculture in Belgium

In 2009, Wouter Meeus, the man who was to become Claeyé ’s mentor, was hired by University College Odisee in East Flanders. The European Union had just launched AquaVlan to move aquaculture forward in Flanders and Holland. At that point, aquaculture was “very small – the research institutes involved in aquaculture could be counted on one hand,” says Meeus.

Fish farming was having difficulty gaining traction. VitaFish, the largest tilapia farm in Europe at the time, had recently failed. With no long-standing aquaculture tradition in Flanders, interest languished. When potential producers did pursue aquaculture projects, they were doomed to a legislative purgatory. Consumer adoption was hard to predict. And then there were the high cost of entry, forbidding operational costs, and a delayed return on investment.

Projects stagnated in the “intention phase,” says Wouter. But the AquaVlan partners, primarily research institutes, were determined to catalyze commercial production.

‘Fork-to-farm’

For the researchers at Aqua-ERF, the AquaVlan project started with selecting a species. They chose burbot, an indigenous freshwater fish in Flanders that had disappeared because of loss of spawning grounds, water quality and overfishing.

Burbot offers a flavor that some compare to American lobster and a firm texture that resembles cod – in fact, it is the only freshwater species that is related to cod.

The researchers selected it “not because it was an easy fish to culture. The other way around, the fork-to-farm principle,” says Wouter.

Burbot had a market not only among a growing number of fish eaters in Belgium but also with traditional cooks. It plays a prominent role in Gentse Waterzooi, a national treasure in comfort food, which dates back to the 16th century when it was a favorite of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

The Flemish choice of species contrasted with the approach taken by neighbors to the north, the Netherlands, who began culturing tilapia and African catfish. In time, however, those farms went bankrupt because “you cannot compete with Asia,” Meeus says. Burbot, on the other hand, could garner a higher price to offset expensive farming methods because it offered both quality and a tradition.

“It’s also the experience you’re selling,” he says.

But the market is even broader. Its liver, which represents 10 to 12 percent of its body weight under natural conditions, is prized as a delicacy. “It can be sold in the same niche as foie gras,” says Claeyé. The Scandinavians enjoy its roe. And the Swiss use its skin to produce a fine, soft, beautifully patterned leather for watchbands, wallets and other accessories. “It has a lot of potential,” Claeyé adds.

Few precedents, many challenges

As Meeus forged ahead with the design and construction of the recirculating aquaculture system at Aqua-ERF, he also stepped up recruiting and brought Jurgen Adriaen on board as an aquaculture scientist. That was the start of over a decade of research on burbot: reproduction, larval production and grow-out factors.

And Meeus was right about the challenges of raising burbot. They start at spawning, which occurs once a year. As larvae, this species demands live feed. What’s more, they are cannibalistic. But Claeyé has successfully confronted these hurdles and more.

Burbot require temperatures below four degrees Centigrade, and egg incubation takes up to one and a half months – “quite a prolonged period,” says Claeyé. During this time, he’s on the watch for fungi, such as the “dreaded” Saprolegnia. Each day, Claeyé cleans the miniscule eggs, removing dead ones from the frigid water.

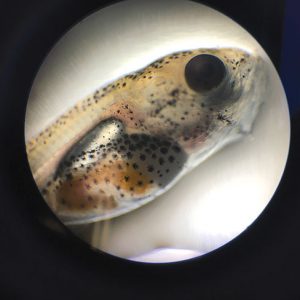

Between hatching and the first feeding, the larvae undergo important developments: yolk sac resorption, swim bladder inflation, and formation of other internal organs. This all occurs as they grow from approximately 2.8 millimeters (mm) to 4 mm – less than half the length of an average human eyelash.

So much can go wrong. “If the larvae haven’t filled their swim bladders, they will waste a lot of energy maintaining their positions. If they have hyperinflated their swim bladders, they will be floating on the surface…and die off.” While constantly monitoring water current, light and pH, he also checks larvae under the microscope.

“Burbot larvae are much more sensitive than other species I’ve worked with,” says Claeyé.

Burbot larvae have a prolonged live feed period, in which they are manually fed artemia – an expensive and time-consuming process. “But it is a prerequisite to get good survival and quality fingerlings,” says Claeyé.

“When we started with larval research, one of the issues was the long artemia period of more than 60 days and high mortality at weaning,” adds aquaculture scientist Adriaen. The challenge was that, although burbot larvae could eat dry feeds, most would not come up to the surface to feed and there was a lack of slow-sinking dry larval feed of 200 micrometers.

But with some changes in the protocols and feeding methods, the Aqua-ERF team has already reduced the artemia period to 50 days, according to Adriaen, “and this can probably be lowered more.”

Cannibalism can also be a major issue, especially during the late larviculture and weaning phases. So, during larviculture, Claeyé manually sorts out the bigger individuals, which tend to be the most cannibalistic. That behavior, including tail biting, occurs if feed is insufficient or stocking density isn’t right.

“Burbot can be quite aggressive feeders,” says Claeyé. Later, burbot are mechanically graded to help manage cannibalism.

Growing guidelines

At Aqua-ERF, researchers also learned they could stock this benthic species with densities of 60kg to 100kg per square meter in a commercial RAS set-up. They hypothesized that the higher density broke a social hierarchy, thereby achieving more equal growth distribution.

During grow-out, optimal water temperatures range between 14 and 16 degrees Centigrade. In RAS, burbot grow to 500 to 600 grams in 12 to 15 months; in flowthrough, it takes 1.5 to 2.5 years.

And the good news is that, after challenging the hatchery as such finicky larvae, burbot later are satisfied with a much more economically attractive diet, yielding a feed conversion ratio of 1:1.

Bright future

The early efforts of the Flemish AquaVlan partners were successful in getting aquaculture “back on the rails” in Flanders, says Wouter, now head of Aqua-ERF.

At this point, he can point to a RAS hatchery and grow facility for jade perch (known also as omega perch because of its plentiful Omega-3 fatty acids), a hatchery for pike perch, a biofloc-based shrimp farm, a burbot hatchery and some small-scale burbot grow-out units.

“There are some new projects in the pipeline, so I expect new farms in the near future,” he adds. With a decade of knowledge to fuel their success, he appears confident production will soon reach “critical mass” to prove aquaculture is viable in Flanders.

No doubt the 24-year-old Claeyé will be playing a key role. This year, Aqualota produced 50,000 fingerlings. The company aims to “at least” double production next year and triple it by 2022.

At the side of the young Claeyé will be his father, his co-founder, who assists in fingerling production. “He is also interested in aquaculture and decided to help me both financially and practically, for which I’m very grateful,” says Claeyé.

In addition to the space they are leasing at Odisee, they are also renting next door where they are building a RAS to house fingerlings and to pursue some grow-out themselves. The plan is also to relocate the broodstock and the hatchery system there.

And then maybe his father can move his car back into the garage.

Print this page